Sermon for February 11, 2024 -Transfiguration Sunday

Service in Celebration of Black History Month

As I was preparing for today, I spent these past two weeks immersed in news articles, poetry, speeches, and theological writings, all with the hope of learning more about the struggles and the impact that African and Caribbean cultures have had on these shores. And to start, I did what most people do when they start an inquiry, I Googled it. I was very interested in the origins of Black History Month; when did it start, why did it start, and how has that been received and celebrated since its inception?

As far back as I can remember, February has always been Black History Month. And while I am sure I was taught all of these basics since elementary school, those facts have long seeped into the deep of the recesses of my mind, which has left me with a vague recognition that this is important, but with little to back that up. And so, just as Jesus said to his disciples at the Last Supper, it is good to remember, so that we do not forget. Because when we forget, we repeat the mistakes of the past.

The origins of Black History Month date back to February 1926 when Carter G. Woodson came up with the idea of Negro History Week. In the aftermath of the Civil War, Black history was being repressed in many schools, especially across the South. Woodson, whose parents had been enslaved in Virginia, was afraid Black students were not learning about their ancestor's lives, accomplishments and struggles in schools. Because of his own family's economic hardship during his youth, Woodson learned the immense value of education and became passionate about history.

Woodson chose February for celebrating Black History because both Abraham Lincoln and Fredrick Douglass celebrated their birthdays in February. Lincoln's birthday is Feb. 12, and Douglass, who was born enslaved and did not know his actual birthday, celebrated it on Feb. 14. Because of the connection with Lincoln, the U.S. President who signed the Emancipation Proclamation, and Douglass, a prominent Civil Rights leader and abolitionist, the African American community already celebrated in the second week of February – making it an ideal time to encourage a focus on Black history.

Woodson spent his life advocating for excellence in education for Black students, and for him, Black History Month was just one thread in a much broader goal: Ensuring Black history wasn't erased and that Black students would have equal access to education. And what makes this month all the more important is that even today in classrooms across the States Black history is being erased from curriculums and cultural expressions suppressed. In Houston, Texas, a teenager has been suspended from school for most of this academic year because he refuses to cut his hair which is in traditional locs, even though they violate a specific dress code that disproportionately affects young Black teenagers of all genders. In a school district in Florida, signed parental permission slips were required for students to opt into Black History Month education. The state board of education in Florida has gone even further by not only removing the Advanced Placement course in African American Studies from all state schools, but they have also actively fought against any diversity, equity, and inclusivity initiatives that would benefit people who have continuously been negatively impacted by the systemic racism that is baked into the structures of every American institutions. Much like the Pax Romana of Jesus’ day, the desire for the status quo of oppression and repression remains.

These themes of suffering under the yoke of oppression, of hope and liberation perhaps shine most brightly through the songs and poetry of of Black artists and authors. As I navigated through a wealth of poets American, Caribbean, and African alike, I was provided with deeply moving lyrical expressions of their experiences of being Black in their respective contexts. Each poem I read was filled with suffering and longing; a suffering that brought tears to my eyes and a longing faith that things will get better.

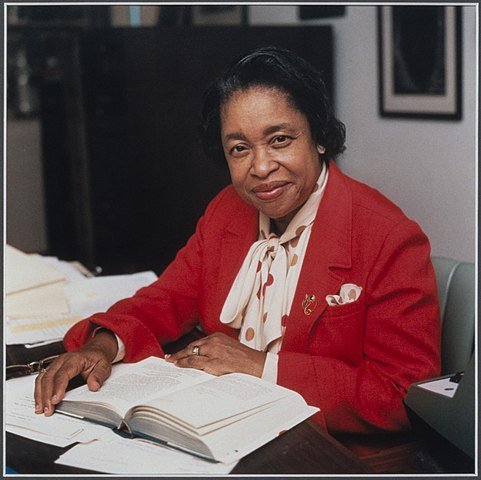

Margaret Walker.

In her 1942 poem For My People, Margaret Walker captures that suffering in different ways, from her slave roots to her own childhood in 1920’s segregated Alabama to the struggles of her present time. But, like any good psalm of lament, the poem ends in a hopeful longing for change and transformation. She writes in part:

For my people everywhere singing their slave songs

repeatedly: their dirges and their ditties and their blues

and jubilees, praying their prayers nightly to an

unknown god, bending their knees humbly to an

unseen power;

For my people lending their strength to the years, to the

gone years and the now years and the maybe years,

washing ironing cooking scrubbing sewing mending

hoeing plowing digging planting pruning patching

dragging along never gaining never reaping never

knowing and never understanding;

For my people standing staring trying to fashion a better way

from confusion, from hypocrisy and misunderstanding,

trying to fashion a world that will hold all the people,

all the faces, all the adams and eves and their countless generations;

Let a new earth rise. Let another world be born. Let a

bloody peace be written in the sky. Let a second

generation full of courage issue forth; let a people

loving freedom come to growth. Let a beauty full of

healing and a strength of final clenching be the pulsing

in our spirits and our blood. Let the martial songs

be written, let the dirges disappear.

“Let a new earth rise. Let another world be born.” That hopeful longing for a radical and holistic transformation of our world has been at the heart of Liberation and Black Theology since its inception. In delving into the writings of African American theologians like Martin Luther King Jr. and Howard Thurman, I came across the works of James H. Cone, a prominent African American theologian. In his seminal work, A Black Theology of Liberation, Cone writes:

“It is my contention that Christianity is essentially a religion of liberation. The function of theology is that of analyzing the meaning of liberation for the oppressed so they can know that their struggle for political, social, and economic justice is consistent with the gospel of Jesus Christ. Any message that is not related to the liberation of the poor in a society is not Christ’s message.”¹

Elsewhere he writes that “Exodus, prophets and Jesus – these three – define the meaning of liberation in black theology.”² And that makes sense. Exodus is the grand epic of liberation of an entire people, specifically chosen by God, who were freed from the yoke of slavery and who underwent a process of transformation before entering into the Promised Land flowing with milk and honey; a hopeful vision of what could be. The prophets were considered the mouthpieces of God, uttering the will of God to the people, especially in times when the people strayed too far from the will of God. Prophets spoke truth to power and often paid for it with their lives. And then of course there is Jesus, who through his words and actions, offers a glimpse of the upside-down Kingdom of God, the new Jerusalem, the new Promised Land.

I guess it is a good thing then that today we have all three in our gospel story of the Transfiguration. With Moses and Elijah appearing alongside a transfigured Jesus shows the disciples that Jesus is the embodiment of both the Exodus and prophetic traditions. Through Jesus, not only is he the fulfillment of the Hebrew prophetic messages, but there is also a new freedom, a liberation, an exodus from the old ways to something new that is found in following Christ.

The temptation for the disciples is to want to stay in this mountaintop moment, to capture it and hold onto it as long as possible. When we experience those moments we can use them as fuel for our journey back down into the valleys of life, carrying that energy and light down into the darkness of the valleys below.

This story reminds us that the work of God is not over. Bringing about the kingdom of God, bringing about transformation in ourselves and in the world around us is a constant endeavor. So let us find strength in those who have gone before us, give thanks to God for how far we’ve come, all the while acknowledging that there is still plenty of work to be done if we want to transform our world.

Amen.

¹ J. H. Cone. A Black Theology of Liberation. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1970.

² Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody: The Making of a Black Theologian. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2018.